On a winter’s evening in 2019, Wellington nurse Catherine Flanigan crossed the deck of the Ocean Viking with a concerned look in her eyes and determination in her gait.

While other New Zealanders sailing the Mediterranean that night might have been taking a relaxing cruise, chasing the last of the summer sun and sight-seeing at historic places, Catherine, 35, was dressed in full heavy-duty marine rescue kit – complete with hard hat, headlamp and gloves – preparing to nurse women with severe burns.

Just minutes earlier, she’d been at sea on a rigid hull inflatable boat, helping to rescue dozens of refugees and migrants who had risked their lives to flee Libya in the hope of finding a better life in Europe. Then she was called back to the Ocean Viking, the ship previously used by the charity Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF, aka Doctors Without Borders) on humanitarian missions in the Mediterranean. Two fellow medics were trying to save the life of a woman who was unresponsive because of fuel burns and Catherine was needed to help others with similar serious burns.

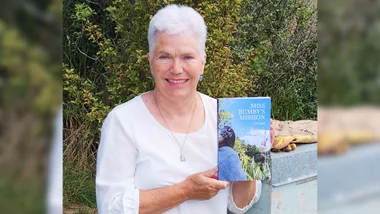

Catherine’s at the ready to help on the Ocean Viking.

She says seeing the boats people leave North Africa on is heartbreaking. “They’re essentially just inflatable dinghies, often of terrible quality and so overcrowded,” she explains. “When the fuel that is tipped into the motor mixes with the sea water, it really burns the skin

“The women and children are usually put in the middle of the boats because it’s supposed to be safer, but that’s where water starts overflowing into, so quite often you’ll see – particularly women and children – with these really severe fuel burns. They don’t really realise it’s happening, but after a few hours of sitting in this kind of mixture, it corrodes away. It’s like a chemical burn.”

In recent years, hundreds of thousands of refugees and migrants have fled appalling situations – war, dictatorships and famine – in the hope of making it to Europe to begin new lives. Most attempting the dangerous Central Mediterranean route leave via Libya, where refugees and migrants face arbitrary detention, extortion, torture and all too often death.

Search and rescue in the Mediterranean.

“Multiple survivors have said to us that they knew it was dangerous, but they left anyway because they would rather die than stay in Libya. It’s the mums with the really young children that tend to stick with you.

“The thing that can be difficult to comprehend is that they’ve often tried several times to cross – it might be their third, fourth or fifth attempt. Often, they’ve had difficult crossings where they’ve seen their friends and relatives drown in front of them, but they’re willing to risk it again and that tells you how bad things must be.”

Since joining MSF in 2018, Catherine has completed four search-and-rescue missions in the Mediterranean, spent 12 months nursing in South Sudan and had two assignments to the Al-Hol refugee camp in Northern Syria. Wanting to share these stories to highlight the plight of desperate refugees and migrants is a strong driver for Catherine to talk via Zoom to Woman’s Day from her base in Gothenburg, Sweden.

Fenced in: A young girl at Al-Hol camp in Syria.

Raised in Wellington, she started studying law but switched to nursing after hearing stories from friends about their action-packed education. Right from her first classes at training institution Whitireia, Catherine knew she had made the right choice.

After graduating, she worked at Wellington Regional Children’s Hospital, but short stints volunteering in East Timor and in Papua New Guinea made her want to contribute more.

In 2018, she travelled to Sydney to interview for assignments with MSF, which provides medical assistance to those affected by conflict, epidemics, disasters or exclusion from healthcare. Started in 1971, MSF now has 67,000 staff members of 169 nationalities working in more than 70 countries. In the past five years, 58 New Zealanders have been on assignment with the medical charity working

in a variety of roles.

An MSF malaria outreach team at a refugee camp in South Sudan.

She pays tribute to the local staff she has met in each location MSF has assigned her to. “It’s not like they’re missing out on great staff and they need us to come in to do everything for them. Everywhere I have worked, there are fantastic medical staff, so it’s more about supporting them and adding resources.”

Catherine acknowledges it can be tough to get used to life when she returns to Aotearoa to work, but MSF has procedures to help with those readjustments. However, for the foreseeable future, she’s committed to this work and is completing a Masters in Humanitarian Practice through the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine.

“Every time I leave a project, I’m thinking, ‘What could I have done better? How could I manage that better next time?’ So it’s about helping me improve myself.”