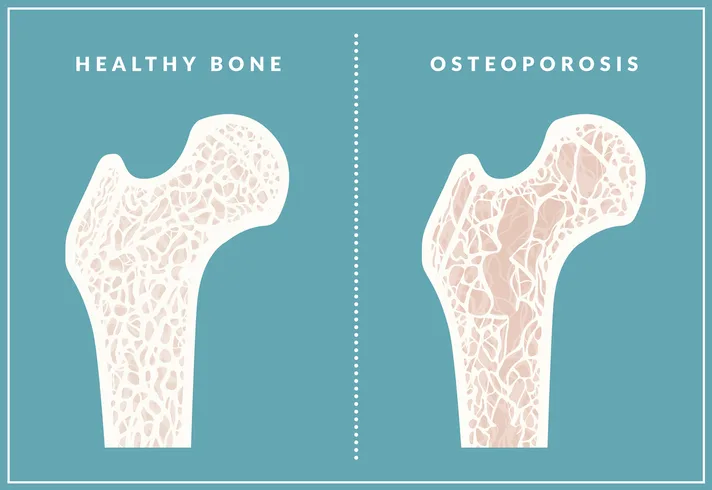

Osteoporosis is often described as an invisible disease. We can’t see our bones. We can’t feel how strong they are. They’re out of sight, out of mind. Until they break.

“Many people think osteoporosis is something that happens ‘when we’re older’ but the peak incidence of fragility (or unexpected) fractures is under the age of 75,” says Professor John Eisman from the Garvan Institute.

“This is a relatively common problem in our population. And after age 75 you have a one in two chance of having a fragility fracture.”

There’s a cluster effect, too. Your first fracture may mend well. However, for the next five years your risk of another fragility fracture grows two or three-fold.

The problem, say experts, is that we’re not doing enough to treat the underlying cause of fragility fractures – our thinning bones. Treating osteoporosis is crucial because although broken bones heal, our risk of death still rises.

“We’re two to three times more likely to die within a few years of a fragility fracture than other men and women of the same age – and we don’t understand why,” says Professor Eisman.

“Treating thinning bones halves that risk. And despite sporadic headlines about adverse reactions, they are very rare.”

Misconceptions continue to trip us up.

After all, we’re told we stop building bone by age 30. That leaves a gaping hole of 30 to 40 years for us to hope for the best until we might start to experience the effects of osteoporosis. That’s the common logic, anyway.

It’s true that we reach our peak bone mass by age 30, then old bone starts to break down faster than new bone can form. However, we can still replace most of what’s lost each day.

Think of it as a bank. You made daily deposits up to age 30 and accumulated a healthy balance – in other words, your peak bone density. Then your body started to make bigger withdrawals. You can never increase your peak bone density but you can keep topping up your savings to maintain it at the highest possible level throughout your life.

While post-menopausal women and men over 60 are most likely to have osteoporosis, there are other surprising risk groups, according to Professor Peter Ebeling of Monash University.

For instance, women and men who’ve had hormone treatment for breast or prostate cancer. Also, anyone who has a chronic disease (such as kidney or liver diseases, thyroid problems and coeliac disease) or takes certain treatments (such as corticosteroids for asthma/arthritis/inflammatory bowel disease) may face thinning bones.

Add to that anyone who exercises rarely and takes in little calcium, vitamin D and protein.

“There are no symptoms until a bone is broken; however, tell-tale signs include loss of height or Dowager’s hump,” says Professor Ebeling.

“The most important sign is a broken bone after minor trauma such as falling from standing height or lower.”

Treatments include weekly or monthly tablets, yearly infusions into the veins or twice-yearly injections. Hormone therapy for menopause can also help and, as a last resort, an injected bone-forming medicine.

“However, none of these can cure osteoporosis – it’s a lifelong disease and needs long-term treatment,” Professor Ebeling adds.

Since three-quarters of your risk for osteoporosis is inherited, your family history (and in the future, genetic testing) is an excellent indicator. For now, bone density scans are crucial – and long before we’re 70.

Know your bones

“Bone density starts to drop before women are completely menopausal,” notes Professor Eisman. “That’s a good time to have bone density checked.”

Start by heading to osteoporosis.org.nz and taking the one-minute test.

What does a scan involve? You lie down while the scanning arm hovers over your body.

What do they cost? Your doctor will write a referral to your nearest bone scan service and the cost is around $100-$150.

What about radiation? There is a small amount of radiation exposure but less than what you’d get on a flight from Auckland to Christchurch.

How much calcium is in dairy-free milk?

Dairy products are one way to help keep up our calcium intake, but what about dairy-free milks?

We consulted dietitian and nutritionist Rebecca Gawthorne to find out how they stack up.

Almond: Low in saturated fat and contains healthy heart fats, but also low in protein and calcium; often sweetened. Choose one that is unsweetened and fortified with calcium.

Soy: The best alternative to dairy milk as it is the most nutritionally balanced with good protein content. Choose a calcium fortified version

Rice: Low allergy risk, but it lacks nutrient variety. Could be good in a pre-workout smoothie due to the high natural carbohydrate content. Choose a calcium fortified variety.

Oat: Low in protein and not nutritionally balanced (also contains gluten so not suitable for coeliacs). Choose a calcium fortified oat milk.

Dairy: Nutritionally good option. Provides protein, calcium and essential nutrients, although also some saturated fat and cholesterol.

For more health news and advice pick up the latest issue of The Australian Women’s Weekly, onsale now.